The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons On Wealth, Greed, and Happiness

As a former journalist and partner at a venture capital fund, Housel turns his viral article on the cognitive and emotional narratives we have around money into a highly readable and practical guide for staying sane and being more effective about money.

Today I want to talk about Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons On Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel. This book started as a viral article on the Collaborative Fund blog (where Housel is a partner) and has a whopping 33k reviews on Amazon (4 Hour Workweek only has 25k), making it an absolute must-read.

It's one of those books that's very low on the technical aspects of finance and investing, and very high on the stories and principles of how to engage with money in a practical and helpful way. Please enjoy my book notes on the topic.

1. Health and Wealth

"Two topics impact everyone, whether you are interested in them or not: health and money."

Health and wealth are the two topics that impact you, even if you have no interest in them. It doesn't matter if you don't care about health, the facts about health will impact your life.

Even if you don't follow the stock market, how money works, you are impacted by this because you need money to eat, to live. That's why it's so important to spend time becoming financially literate.

2. Making vs Keeping Money

"There are a million ways to get wealthy, and plenty of books on how to do so. But there’s only one way to stay wealthy: some combination of frugality and paranoia."

We often conflate these two things but making money and keeping money are two different things. Making money often involves taking risks, having big ideas, and being bold. Keeping money is about being steady, disciplined, focused. \

Throughout the book Housel walks through a bunch of examples of smart people who are able to make a ton of money, but did not have the emotional fortitude, thoughtfulness, and stability to keep that money. And so they ended up losing all their money.

3. Money Trauma

"In theory people should make investment decisions based on their goals and the characteristics of the investment options available to them at the time. But that’s not what people do. The economists found that people’s lifetime investment decisions are heavily anchored to the experiences those investors had in their own generation—especially experiences early in their adult life."

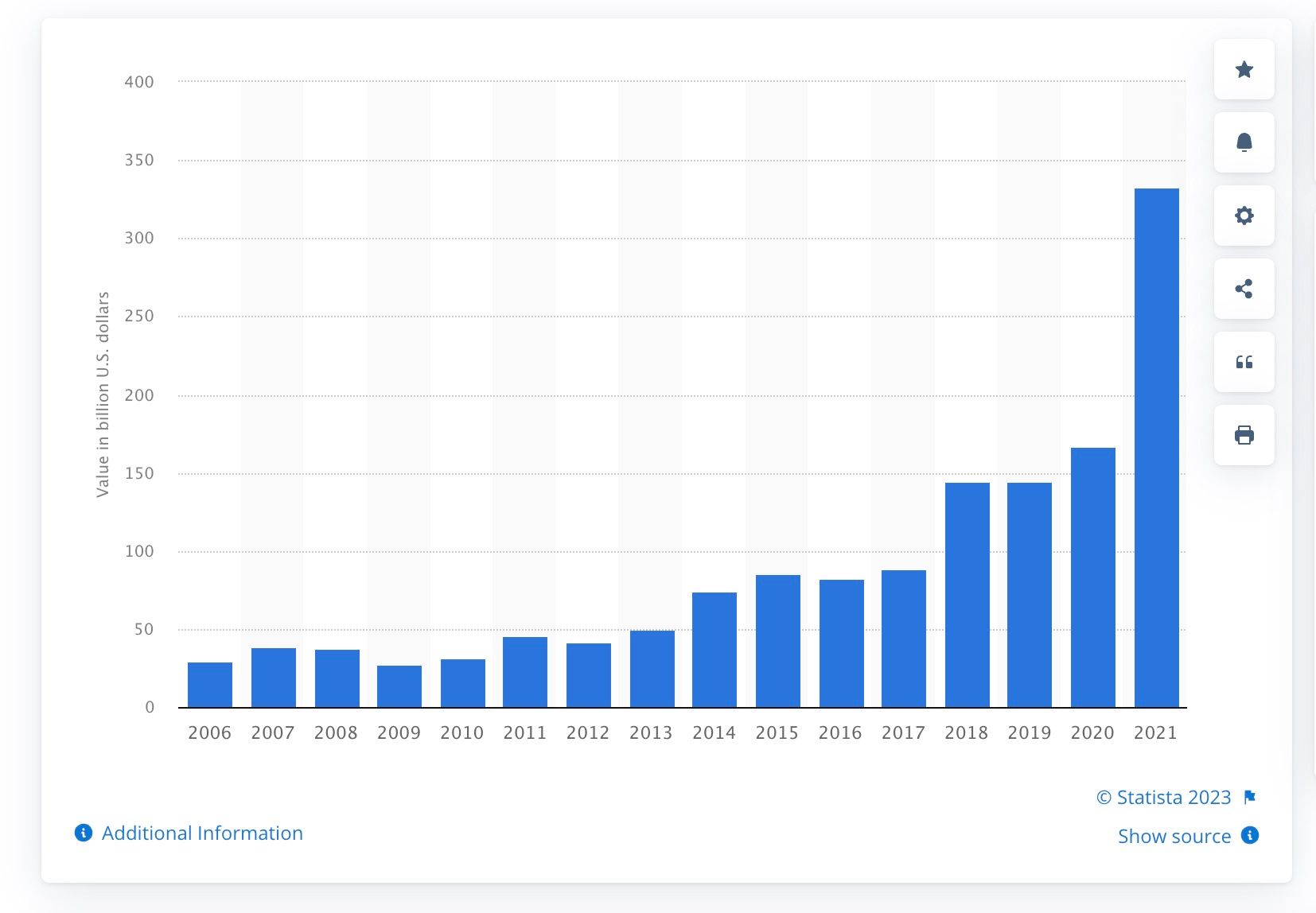

There are young people who are in Silicon Valley today who prior to late 2022, had never been in a significant recession or decline in funding because VC funding have been largely on the rise since 2007.

My own parents grew up with not a lot of focus on investing in the stock market. They put some money into their 401k, things like that, but they also bought a house. The house was a big way that they saw that they could accumulate money and they just tried to save a lot of their salary.

My response was to go against that and focus, not on saving, but on making more money. There's two modes of thought to that. There's one mode that's yes, you can always make more, there's only so much you can save. The other angle of this is that you can always spend more than you make, right?

4. Everyone Does Money Differently

"People do some crazy things with money. But no one is crazy. Here’s the thing: People from different generations, raised by different parents who earned different incomes and held different values, in different parts of the world, born into different economies, experiencing different job markets with different incentives and different degrees of luck, learn very different lessons."

This idea that what looks irrational to you can be totally rational or at least reasonable for somebody else. That can be anything from a difference between day traders to long-term investors to people who don't invest in the market at all.

"Americans spend more money on lottery tickets than on movies, video games, music, sporting events and books combined, and it's mostly by poor people."

Housel points out that many poor people value the hope that lottery tickets bring because it's hard to get excited about the idea of putting a dollar or two away every week and hoping that over a 50 year period, that can compound to something real. The lottery is a chance to be whisked away to some fantasy where you all of a sudden are incredibly wealthy. While that fantasy is unlikely to come true, it still feels good in the moment and this shouldn't be judged when it's such a common response to scarcity.

5. Old Brains vs New Money

"Let me reiterate how new this idea is: The 401(k)—the backbone savings vehicle of American retirement—did not exist until 1978. The Roth IRA was not born until 1998. If it were a person it would be barely old enough to drink. It should surprise no one that many of us are bad at saving and investing for retirement. We’re not crazy. We’re all just newbies."

The 401k has only been around for 50 years. So a lot of these financial vehicles have not been accessible to normal people. They had other ways of ensuring their livelihood.

Dogs have been domesticated for 10,000 years and they're still a lot like wolves in many many ways. Meanwhile, we've had these financial instruments for 20 to 50 years and we expect people to be super sophisticated with them when that makes no sense in reality.

6. Luck Matters

"Luck and risk are both the reality that every outcome in life is guided by forces other than individual effort... They both happen because the world is too complex to allow 100% of your actions to dictate 100% of your outcomes."

The role of luck and risk in our lives. Luck, it's more like positive, random things can happen, that can make our lives successful. Risk is the other side of that coin, that bad things can happen that we don't expect and can really screw us over. We are subject to both those things on a regular basis.

Someone asked Nobel prize winning economist Robert Shiller "what do you want to know about investing that we can't know?" He said: "the exact role of luck in successful outcomes" because it is so hard to pinpoint.

7. Genetic Wealth

"Economist Bhashkar Mazumder has shown that incomes among brothers are more correlated than height or weight. If you are rich and tall, your brother is more likely to also be rich than he is tall."

The genetic association of wealth was so fascinating. Incomes among brothers are more correlated than height and weight. Education, your family background a lot of these things play a role. But you meet two rich brothers and they will tell you it has everything to do with how hard they work. So funny.

8. Fortunes Are Often Made by Outlaws

“That attitude is why he was so successful. Laws didn’t accommodate railroads during Vanderbilt’s day. So he said “to hell with it” and went ahead anyway."

Both Lyft and Uber flouted the law when it came to ride hailing regulations. That's how they built the companies that are as successful as they are today. I built a ride sharing company called Ridejoy—but what these guys were doing seemed so clearly illegal, that we were afraid to pivot into that. Not saying that we could have been Lyft or Uber just saying that we weren't even ready to enter something that was so obviously against regulations.

Housel talks about Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of the incredibly wealthy Americans of the past, who ran a series of railroads. One of his advisors tells him that all these transactions that he'd agreed to broke New York state law.

Vanderbilt says, "My God, John. You don't suppose we could run a railroad in accordance with the statues of the state of New York?"

He was willing to deal with whatever enforcement problems come along. That is not something that most people can afford to do. They believe they'll be punished either right away or later on and the costs are just too high to stomach.

9. Success Is a Lousy Teacher

"After my son was born, I wrote him a letter that said, in part:... I want you to be successful, and I want you to earn it. But realize that not all success is due to hard work, and not all poverty is due to laziness. Keep this in mind when judging people, including yourself."

This sense of what should you learn from success and what should you learn from failure? Bill Gates says "success is a lousy teacher, it seduces smart people into thinking they can't lose". The quote is so perfect for this moment where Elon was forced to buy Twitter for so much more than it had become worth in the stock market.

When you're successful you're never as good as people say you are, and when you fail, you're never as horrible as the failure may suggest. So how do you make sure that when you succeed, you can retain some of that success?

The key is to not get wiped out. You can go down and hopefully you don't go down too much because, if your portfolio falls by 50%, you need to double your money to get back to neutral. So losses hurt a lot more than gains can.

10. Know When To Stop

"What Gupta and Madoff did is something different. They already had everything: unimaginable wealth, prestige, power, freedom. And they threw it all away because they wanted more. They had no sense of enough."

A lot of wealthy people get into trouble when they can't stop. Housel talks about Rajat Gupta, who was a CEO of McKinsey and retired to take on roles with the UN, World Economic Forum. A wealthy man who sits on the board of several public companies. He'd grown up on the slums of India yet by 2008, he's worth a hundred million dollars.

But he is surrounded by people who are billionaires and all of a sudden he's going how come I'm not a billionaire? I want to be a billionaire. He begins an insider trading scheme, eventually he gets caught and goes to jail for two years and more importantly, will always live with a tarnished reputation.

On one hand, he deserved his punishment and more, but on the other, it's truly sad because why did he need to do that? Like Bernie Madoff, Gupta ruined a perfectly good life in order to make more money. He didn't know when enough was enough.

11. What is Invaluable?

"Warren Buffett later put it: To make money they didn’t have and didn’t need, they risked what they did have and did need. And that’s foolish. It is just plain foolish. If you risk something that is important to you for something that is unimportant to you, it just does not make any sense."

Your money is valuable. But what is invaluable? Reputation is invaluable. Freedom and independence is invaluable. Time with loved ones is invaluable. Good health is invaluable.

When you know what is valuable versus what is invaluable, you are able to stop taking stupid risks in order to protect what is invaluable versus trying to get what is just valuable.

12. The Power of Patience

"As glaciologist Gwen Schultz put it: “It is not necessarily the amount of snow that causes ice sheets but the fact that snow, however little, lasts.” The big takeaway from ice ages is that you don’t need tremendous force to create tremendous results."

Patience and discipline over time is a superpower. One of Housel's great points is the power of compounding. He makes this example of hedge fund manager James Simons who runs a company called Renaissance Technologies compounded at 66% annually since 1988. Compare this to the stock market, which grows 9% annually on average. Simons is 733% better for decades.

Warren Buffett has only done 22% annually, AND YET: Simons is only worth $21 billion, 75%, less rich than Buffet because Simons did not start really hitting his stride until he was 50. Whereas Buffet has been compounding for 70 years.

A year of growth, you're not going to see that much. 10 years, you start to really see something. And then in 50 years something extraordinary can be created. But you have to be unbreakable. Being financially unbreakable, not allowing any of your risks to wipe you out.

13. Keep Shooting

"In 2018, Amazon drove 6% of the S&P 500’s returns. And Amazon’s growth is almost entirely due to Prime and Amazon Web Services, which itself are tail events in a company that has experimented with hundreds of products, from the Fire Phone to travel agencies."

Success is hard. You got to take a lot of shots to get something big. We all know Walt Disney as an incredible creator of this enduring legendary franchise. But it was really hard for him to break through. He spent years making cartoons that people liked, but didn't make any money. By 1938, he had made 400 cartoons. His first studio went bankrupt. And then he does Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.

I hope I don't have to do 400 newsletter issues before I make it big, but I suppose it'd be worth it if I could do a Snow White, which mades $8 million which ins $168M in 2022 dollars. All the debts erased and then some. And that was just the beginning of his rise.

14. How to Buy Happiness

"The most powerful common denominator of happiness was simple. Campbell summed it up: Having a strong sense of controlling one’s life is a more dependable predictor of positive feelings of wellbeing than any of the objective conditions of life we have considered."

Happiness is autonomy. He cites this one researcher who talks about this idea that having a sense of control over one's life is the strongest predictor for happiness. If you can live within your means, then you can control your life. And by controlling your life, you can reliably feel good feelings.

15. You Can't Spend It All

"Wealth is just the accumulated leftovers after you spend what you take in. And since you can build wealth without a high income, but have no chance of building wealth without a high savings rate, it’s clear which one matters more."

Wealth is what you have left over after you spend money on things. Compounding savings is about not spending money, not consuming it on things that won't have value in the future. Rihanna once sued her financial advisor because she spent a ton of money on things and didn't have a lot of money left over. And he said, was it really necessary to tell her that if you spend money on things, you will end up with things and not money.

Dude is not going to get hired back after that one, but it's real. My parents were able to carve out a comfortable life because they had a high savings rate. My own savings rate, not as high, my income, much higher, but will I be able to translate my income into savings and savings into investments and investments into wealth is something that is still an ongoing challenge and effort.

16. Flexibility >Intelligence

"Just over 100 years ago 75% of Americans had neither telephones nor regular mail service, according to historian Robert Gordon. That made competition hyper-local. A worker with just average intelligence might be the best in their town, and they got treated like the best because they didn’t have to compete with the smarter worker in another town. That’s now changed."

Housel talks about how the world used to be hyper-local—if you were the best blacksmith, electrician, piano teacher—you could do well for yourself because you were the number one person in your town and you could command value that way. But now with the internet and with globalization, we can compete with anyone, especially when so much of what we do is digital.

You could be reading any one of the billions of newsletters, emails, short form videos, or streaming movies/shows out there. You have nearly infinite choice. I'm competing with everyone to make the best possible way to spend your time.

"Intelligence is not a reliable advantage in a world that has become as connected as ours has. But flexibility is. In a world where many previous technical skills have become automated, competitive advantages tilt towards nuance and soft skills like communication, empathy, and perhaps most of all flexibility."

This feels more true than ever given the rise of impossibly intelligent generative AI.

17. The Future Is Full of Surprises

"Stanford professor Scott Sagan once said something everyone who follows the economy or investment markets should hang on their wall: “Things that have never happened before happen all the time.” History is mostly the study of surprising events. But it is often used by investors and economists as an unassailable guide to the future. Do you see the irony? Do you see the problem?"

The world is surprising and you will continually be surprised and your predictions will not work out. This means that you need to build in room for error, for redundancy—because things that you never see coming can end up dramatically changing your life.

9/11 prompted the federal reserve to cut interest rates, which drove a housing bubble, which led to the financial crisis, which led to a poor job market, which meant a lot of people went to get a college education and take on student loans.

"We tend not to think that 19 hijackers are going to create a society full of indebted college grads, but that's what happened. The things that are going to change the world are not things anybody sees coming."

I don't think most people in 2005 would realize that their world would be changed so much by this iPhone or Android that everyone has in their pocket. And who would have thought in 2021 that 18 months later, we'd all be having our collective minds blow by GPT-4?

18. Move On

"Jason Zweig, the Wall Street Journal investment columnist, worked with psychologist Daniel Kahneman on writing Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow. Zweig once told a story about a personality quirk of Kahneman’s that served him well: “Nothing amazed me more about Danny than his ability to detonate what we had just done,” Zweig wrote.He and Kahneman could work endlessly on a chapter, but: The next thing you know, [Kahneman] sends a version so utterly transformed that it is unrecognizable: It begins differently, it ends differently, it incorporates anecdotes and evidence you never would have thought of, it draws on research that you’ve never heard of."

Try to have no sunk costs. We all get psychologically invested in things that we spend time on, but the logical thing to do is to let go once you realize that your future is better off without something.

The past already happened, it's over. The future is all that matters. Now sometimes sticking with something that you did in the past might make sense because it allows you to tell a better story of the kind of person that you are. But don't confuse that with the idea that you've already spent so much time on something that you need to just keep doing it, even though it's clearly benefitting you much anymore.

Try to have a clean slate every day, every year, whatever you're working on, you can start over if that's what's best for you.

19. Optimism Sounds Dumb

“For reasons I have never understood, people like to hear that the world is going to hell.” —Historian Deirdre McCloskey"

In his book Factfullness, Hans Rosling notes that nearly everyone he asks thinks that the world is more frightening, more violent, and more hopeless, in short, more dramatic than it really is. In reality, the world has gotten better throughout human history, at least that last two, 300 years. COVID, recessions have all been relative dips. But still, there are some silver linings already that we see from COVID in such as how we can now do mRNA vaccines for many other diseases.

News of bad things travels fast travels far gets splashed in the headlines. Whereas news of good things that are slowly improving don't really make headlines because there's no dramatic thing.

One great example of this is the rate of heart disease in the United States. In the last 50 years we could have had a Hurricane Katrina five times a week, every week for the last 50 years. We would have still offset all those deaths with the amount of lives that we've saved with improving heart disease. But that doesn't make the news. As long as we protect ourselves from the tail risks and the downsides, we should be able to look forward to a better future.

20. Success is Always Unlikely

"I know people who think it’s insane to try to beat the market but encourage their kids to reach for the stars and try to become professional athletes. To each their own. Life is about playing the odds, and we all think about odds a little differently."

Life is about confronting risk, trying to get lucky, trying to protect yourself from bad things and in the end. going after things that you believe you can successfully achieve. Any kind of success is statistically speaking, less likely than not getting that success. Becoming a bestselling author, a unicorn startup founder, a highly sought executive coach aren't things that are super high probability odds for anyone to aspire to. Yet those are the things that I would like to spend time on because I believe in them. At the same time, protecting those downside risks is an important thing for me to do.

How do you want to go after things, knowing that the world is unpredictable and being comfortable with the uncertainty that is fundamental to our lives. That is what the Psychology of Money is about. I hope you check it out.