One of the challenges my clients often face is making decisions and acting in situations of great uncertainty and volatility.

Most founders and high-agency leaders understand in principle that acting with vigor and conviction on an imperfect plan is more likely to achieve success—or at least progress—than trying to craft the perfect strategy. Especially when faced with countless unknowns and constant flux. But sometimes those who are smart often get stuck thinking too much and doing too little.

This situation is difficult enough when working on your own, but it becomes even more complicated with multiple co-founders or key stakeholders. A lot of thrash can occur when leaders disagree on the direction of a project, and whether it is doing “good enough” or not.

Here's how I recommend resolving that dilemma, through a method I call Threshold Checkpoint Goalsetting.

(This is not some wholly original idea, so let me know if you've seen other articulations of it!)

Defining Thresholds

First, identify a key metric that represents the overall success of your project. This should be an outcome-driven KPI such as new users, paid subscribers, or revenue. In PM parlance, it should be your North Star metric.

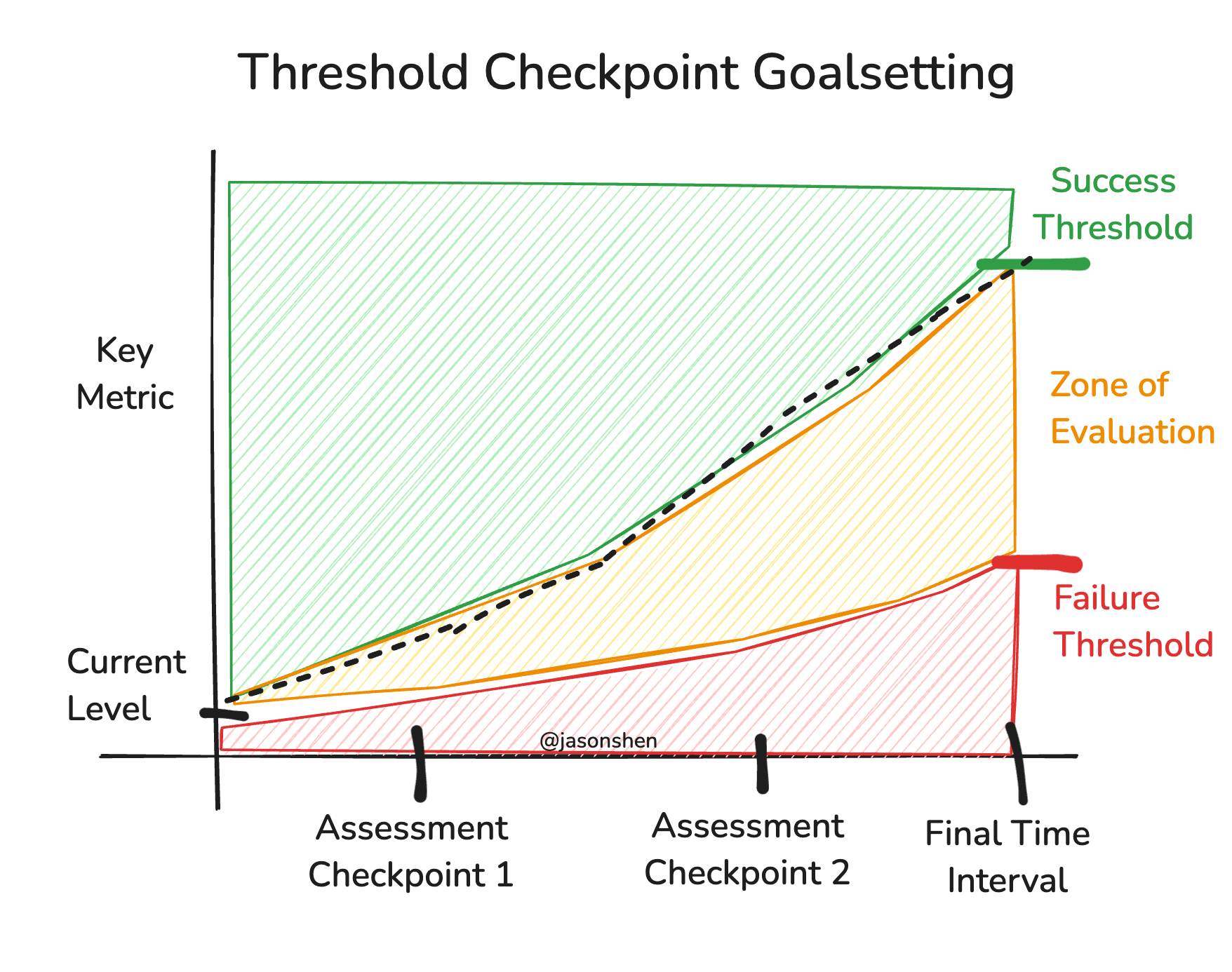

Next, set a hard number for where you want this metric at a specific time interval—one month, one quarter, or one year from now. The number should be ambitious enough that everyone agrees hitting it would make the project an unmitigated win. I call this the Success Threshold.

Next, establish a lower number that everyone would agree represents awful, unacceptable performance. I call this the Failure Threshold. Now you can create a graph charting a path from your current position toward the Success Threshold.

Evaluating Progress

Now you can define when you will assess this metric in order to make decisions about its future. Obviously you’ll the end point of the it’s worth defining a few additional evaluation checkpoints a long the way.

If performance reaches or exceeds the Success Threshold, everything is a go and no further debate is needed. If performance dips below the Failure Threshold for more than a brief period, you shut down the project or make a major directional change.

Between these extremes lies what I call the Zone of Evaluation—the messy middle where you're above the failure threshold but not quite reaching clear success. Here, the team may need to debate strategy and make course corrections aimed at moving closer to the greatness threshold. If you can't make progress upward, you should question whether the project makes sense at all.

By defining success and failure thresholds with clearly defined levels of success and failure, plus scheduled checkpoints to measure progress, you enable your team to work without second-guessing themselves on a daily basis. You create designated times to check status, question strategy, and interrogate the team's process and data. Outside of these checkpoints, the team has room to operate freely and focus on execution.

Putting it into Practice

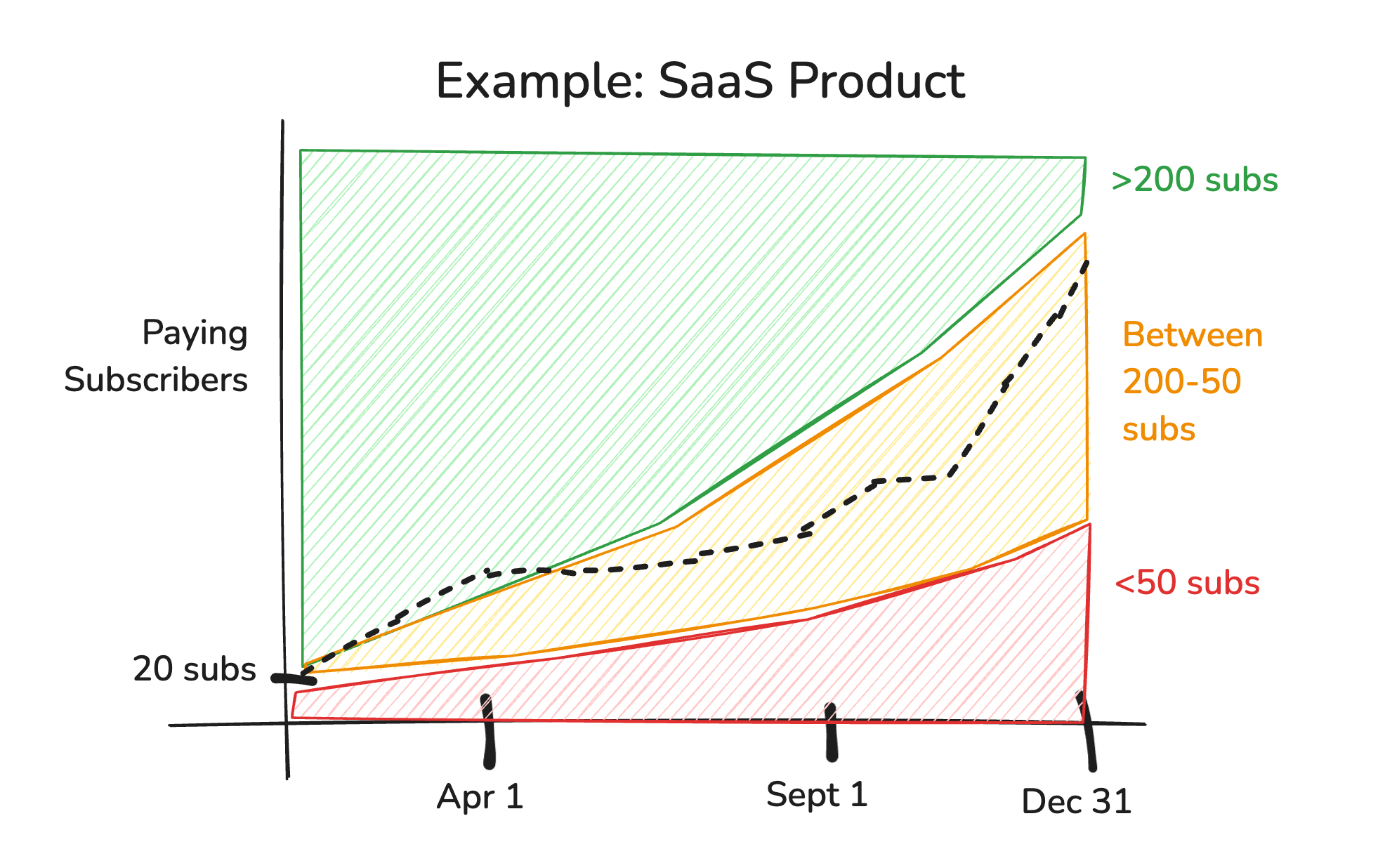

In the below example, we have some kind of SaaS product where paying subscribers is the key metric. Maybe the team has just launched the product and has gotten to 20 paying subscribers, enough to warrant continued investment on the project. But over the course of the next year, how will they know if it's worth continuing to work on this project or shifting towards a new direction?

Well, they set a Success Threshold of 200 or more subscribers. If they can grow from 20 to 200 subscribers by the end of the year, they'd be really happy. They also set a Failure Threshold of 50 or below. If they're at no more than 50 subscribers by the end of the year, it's a clear failure.

Now they have two checkpoints, one in the beginning of April and one in the beginning of September. If their performance dips below the failure threshold, which you can visualize as a path from their starting point, then they know the project is seriously off track and shutting down is maybe the best bet. But if they're in the green zone, then all is good and there should be no questions about moving forward.

Your Turn

Obviously, this is not the only way to make a decision and there are other factors at play than a single metric. You might, in a more sophisticated situation, have multiple metrics. But if you're doing a project from scratch and it's early days and you're a small team, just having one chart is plenty.

Using this method can help you move towards action while ensuring you have systems in place to reassess and redirect yourself. If you find value in this approach, definitely let me know!