This the 76th edition of Cultivating Resilience, a weekly newsletter how we build, adapt, and lead in times of change—brought to you by Jason Shen, a PM, resilience coach, 1st gen immigrant, ex-gymnast, and 3x startup founder.

I am finally back in my place in NYC after 6 months of travel and boy does it feel good. No more living out of a suitcase, away from my beloved Citi Bikes and 45 lbs kettlebell.

But of course it comes with new problems. Like, for instance, am I sitting in a condo that needs furniture surrounded by unopened boxes that need to be unpacked? Absolutely.

Shoutout to new subs: Spk100, Gomex, Yumi, Gwyneth, Cora, Archit, Sunny, Alex, Aundry, Kelvin, Parag, Jordan, Lauren, Tngwy, Ramlah, and Tarik. Welcome to the CR tribe!

-Jason

PS: I have a career spotlight up at Andrew Yeung’s newsletter

PPS: I am going to be switching newsletter platforms soon! Watch out for more info on that in the next issue.

🧠 How a Parenting Expert Learned to Embrace Her Child's Struggle

One of the most beloved administratorss at Stanford was Julie Lythcott-Haims. Before she was the author of the NYT bestseller How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success, she was simply “Dean Julie”. As Dean of Freshman, she lead the loudest cheers and was the warm, friendly, ever-present face that told us we belonged and we would be ok.

Julie publishes a newsletter called Julie’s Pod, which lives on Bulletin, Facebook, excuse me, Meta’s entry into longform, high quality publishing, and I came across one of her articles recently at work [1]: It's Not Your Fault. Okay, It Kinda Is. How to Re-pattern a Family Dynamic to Reduce Kids' Anxiety

In it, she reflects upon how she accommodated one of her then-seven year old son’s picky eating habits by preparing a meal ahead of time. That way, he didn’t have to eat anything unfamiliar at the friend’s BBQ they were headed to and all would be well. But even then, she wondered:

As I held a pot of buttered pasta in my left hand and shook the green can of fake cheese with my right, I'll admit I'd already started asking myself What's your long-term plan, here, lady? Still, the long term wasn’t on my mind as I prepared for the barbecue that night. My boy being satisfied at dinner was what mattered. That, and harmony.

Julie is reflecting on this story because a decade and a half later, The Atlantic would publish an incredibly compelling (if long) piece on childhood and anxiety which features a more extreme version of the same scenario — picky kid, overly accommodating parents, and 3000 meals of turkey meatloaf.

It turns out, childhood depression, anxiety, and suicide have been on the rise in recent years, with a big leap from 2007-2017, with girls suffering the most (1 in 5 reported experiencing major depression in 2017).

The problem is not super clear: maybe smart phones and social media play a role but other countries with high tech usage have not seen a similar spike. The piece focuses instead on how parents inadvertently exacerbate small levels of anxiety by accommodating their children rather then helping them learn to cope on their own. From the Atlantic piece:

Anxiety disorders are well worth preventing, but anxiety itself is not something to be warded off. It is a universal and necessary response to stress and uncertainty. I heard repeatedly from therapists and researchers while reporting this piece that anxiety is uncomfortable but, as with most discomfort, we can learn to tolerate it.

The idea is basically that, like physical training, we can build up our muscle for dealing with anxiety, stress, and uncertainty. Just as a leg in a cast might be protected, but will become incredibly weak, shielding ourselves from discomfort means next time we are simply less capable of handling it.

In my resilience rules framework, I’ve been calling this idea “Embrace the suck”, under the Respond core skill, though I’m considering renaming it “Embrace the struggle” to emphasize our own participation in the experience of hardship. The idea that we have to lean into discomfort, whether in exercise, studying, intimate relationships, is critical to our ability to adapt to change and grow as individuals.

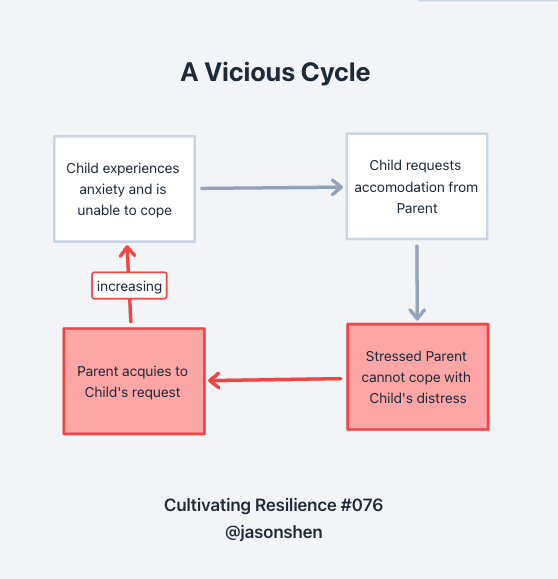

Of course, this is easier said than done. The challenge is that parenting is hard and parents themselves are overwhelmed and this can lead to a vicious cycle. The Atlantic again:

Lynn Lyons, a therapist and co-author of Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents, told me that the childhood mental-health crisis risks becoming self-perpetuating: “The worse that the numbers get about our kids’ mental health—the more anxiety, depression, and suicide increase—the more fearful parents become. The more fearful parents become, the more they continue to do the things that are inadvertently contributing to these problems.”

Beyond the picky eater example, others include:

- Letting the kid stay home when they don’t want to go to school

- Peeing in a bucket in the basement because the kid doesn’t want to be alone

- Taking numerous attempts to get the perfect shoelace tightness

- Buying a different kind of house so that the kid can know where their parents are at all times

Some of these seem absolutely insane to me but then again, I’m not a parent so I don’t want to judge.

But when Julie reflects on reading this piece last year, all those old memories come rushing back to her. I appreciate just how open and vulnerable she is with us in this memory. After all, she is supposed to be the one teaching other parents how to do it!

Whelp. I sit transfixed at my kitchen counter. I feel a tad paranoid. I am, after all, the author of a book that explains that kids who have over-involved parents are more likely to have anxiety and depression, and lack skills and executive function. Yet I am oh-so-clearly the prototypical parent from scenario three, who once made pasta with butter and parm not just for the barbecue at Zach G's house, but, to be honest, for Christmas and Thanksgiving and almost every dinner, really. (I assure you I was just doing what I thought was right, y'all!) And my kid these many years later does have a considerable amount of anxiety. I want to look the other way. Avoid the possible correlation. But I can't.

The big hero of The Atlantic piece is a program aptly named SPACE (Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions) run by Kate Julian and Eli Leibowitz at Yale University. It’s a course for parents to learn how to stop accommodating their children’s requests to avoid anxiety-inducing experiences while supporting their children emotionally with compassion and confidence.

When we shelter kids from difficulty or challenge, he says, we are not merely shielding them from distress; we are warding off the distress that their distress causes us. Moreover, when school and family systems both have a baseline level of stress—when adults are always on high alert—kids don’t get a chance to rebound, and so they resist taking on the sorts of natural and healthy risks that will help them grow. “Et voilà,” he said, “a generation of anxious kids, looking fearfully at the world around them, who become anxious adults. “What happened to us adults that made us the helicopter parents we too often are?”

This idea makes a ton of sense to me intuitively from my days in gymnastics.

You can only get better by doing things that scare you, that are exhausting, frustrating, and at times painful (stretching, injuries). I once crashed on the parallel bars doing a Morisue, a complicated maneuver that involved rotating 1.5 times above the bars and catching the part with my underarms, deeply bruising my shoulders in the process.

I had misunderstood my coach’s instructions and done the skill in a piked position, which rotates slower, rather than a tucked one. My coach was frustrated at my mistake, knew I was in pain, but also didn’t want me to get “psyched out” from doing the skill again.

This isn’t me but another gymnast doing a Morisue and landing not quite well. You can imagine how much more painful this would be without pads

He asked me if I had injured myself or was I just in pain. When I confirmed the latter, me made me do the Morisue again, tucked this time. I performed it correctly, and then he let me off to go ice my shoulders. Did it seem harsh at the time? Yes. But I quickly realized he wanted ME to know that I could still do the tucked version of the skill, I had just been dumb and did the wrong thing and thats why I was hurting.

Julie tries to sign up for the 12 week program but it turns out to be overbooked thanks in part to publicity from The Atlantic piece. But still, she attempts to use the ideas from SPACE on her now grown son, the former picky eater, who is now about to graduate from college.

So she shares the article with him, which he recognizes as representing their families dynamic (funny how we ended up most obsessed with the things we ourselves are all to familiar with). Then she apologizes for her parenting mistakes (even though I don’t feel like this is necessarily something worth apologizing for, but respect anyway).

Through the mindfulness practice I’ve worked hard to develop over the past fifteen years, I’m able to notice when my instinct to swoop in and soothe or solve is cropping up, and then I can decide to instead empathize and empower my kid like Lebowitz advises. For example, one morning Sawyer was worried about a forthcoming conversation with his boss and I saw it in his eyes. Lebowitz tells a story of a set of parents whose young adult was back at home with them. When the kid encountered routine difficulties, he advised the parents: “Just say, ‘We trust that you will find your way.’

The story ends with Julie bringing the trio (Dad, Mom, Son) to family therapy to continue working on unpacking the learned habits of anxiety and accomodation. Julie notes that she always consults her kids before writing about them which is more than many parents might say about their own stories of their kids.

I highly recommend both The Atlantic article itself “What Happened to American Childhood,” May 2020 as well as Julie’s newsletter and this particular issue “It's Not Your Fault. Okay, It Kinda Is”

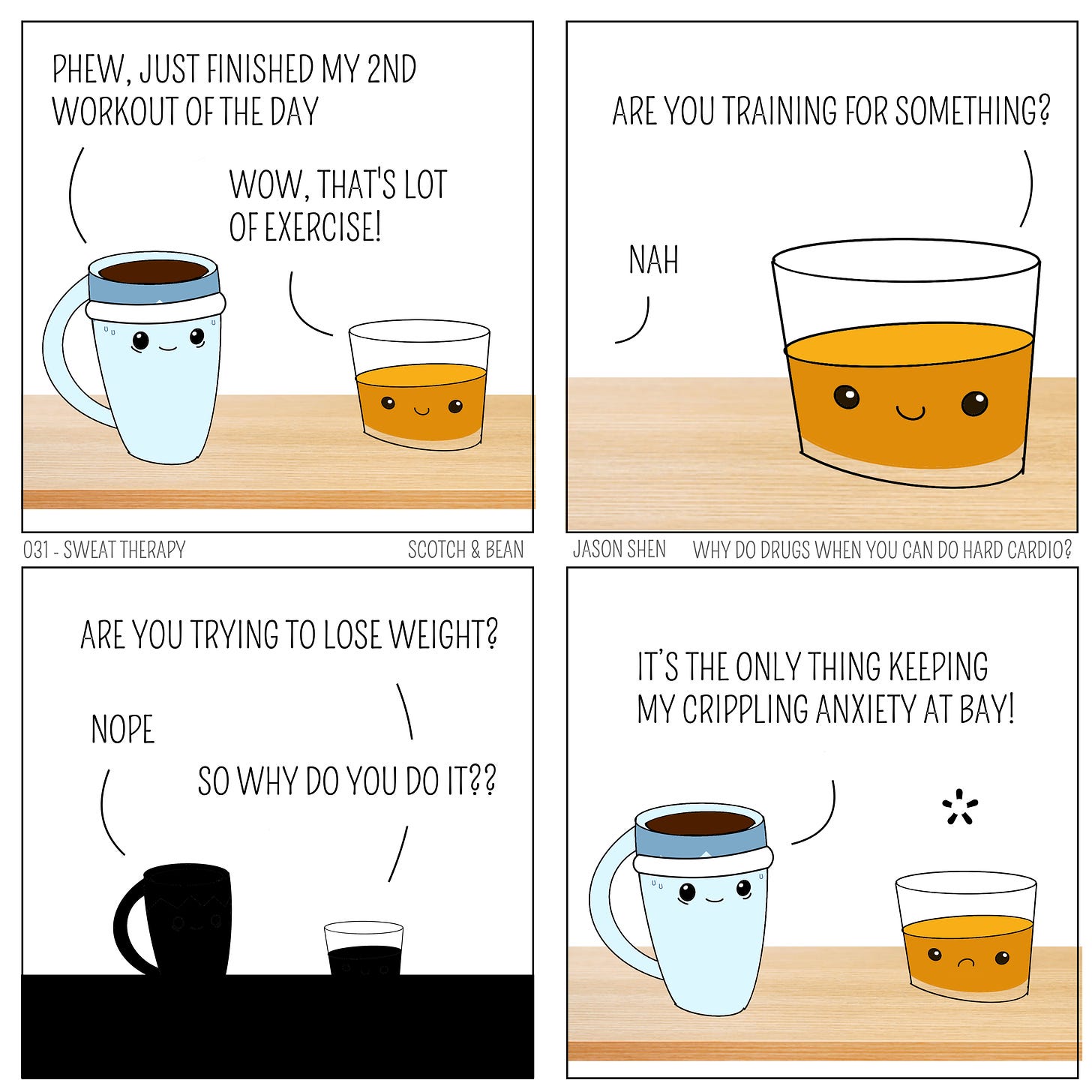

🖼 Sweat Therapy (Scotch & Bean)

👉 Bilal Mahmood for State Assembly

Time for change pic.twitter.com/Oo4SD8rcyY

— Bilal Mahmood 馬百樂 for Assembly 2022 (@bilalmahmood) October 22, 2021

I’ve been helping Bilal Mahmood, my long-time friend and collaborator on 13 Fund run for State Assembly in California. He recently had his campaign video come out and I wanted to share it here. San Francisco politics lean heavily Democratic (similar to NYC) but there’s a distinct progressive, very Left-leaning group that elected official who have not governed particularly competently. The most salient example is of the SF School Board, which kept schools closed throughout the pandemic, spent much of their time renaming schools, and is now facing a recall.

Bilal is an underdog in the race and while I’m biased, I think he brings an openness and transparency to his campaign that you might find interesting even if you don’t follow politics or live in SF.

Like this edition of Cultivating Resilience? Help me reach more people who could use these ideas by sharing it!

[1] My team at Facebook works on a key component of the Bulletin platform.